|

|

|

PLATFORM

|

DS

|

BATTLE SYSTEM

|

|

INTERACTION

|

|

ORIGINALITY

|

|

STORY

|

|

MUSIC & SOUND

|

|

VISUALS

|

|

CHALLENGE

|

Unbalanced

|

COMPLETION TIME

|

40-60 Hours

|

|

OVERALL

|

+ Immense, interesting game world

+ Progressive magic system

+ Compelling music

- Badly-aged mechanics

- Demands copious grinding

- Challenging import

|

Click here for scoring definitions

|

|

|

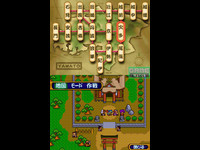

Had the TurboGrafx-16 done a little better outside Japan, Tengai Makyou II: Manjimaru might have seen a localization back in the early 90s. By the time Electronic Gaming Monthly mentioned it in a 1993 issue, the North American market for the system was pretty much dead, and so were the chances of bringing anything that demanded significant effort across the Pacific. Most successful Tengai Makyou games have seen reissues over the years, and among Manjimaru's was one for the DS in 2006 that added information displays on the top screen, which is how I experienced the title. Manjimaru is fondly remembered by those able to play it near its original 1992 release, but coming to it now demands diligence. I saw numerous antecedents of things the Tengai Makyou series would expand upon in future installments, but also had to slog through mechanics that were just fine in the early 16-bit years but are no fun to come across today.

Given that his name is in the title, Manjimaru is sensibly Manjimaru's protagonist. He goes from being a little hoodlum sneaking out of the house to play with friends to having the onus of Fire Clan membership thurst upon him when evil behemoth flowers pop up all over Jipang. Manjimaru accepts his heritage without question and goes forth to beat up the baddies supporting horrible horticulture. Eventually he gains allies to assist: the unrestrainedly flamboyant Kabuki, the quietly powerful Gokuraku, and the reservedly lonely Kinu. A colorful rogue's gallery of antagonists gets in their path to stopping the evil.

By 1992 standards Manjimaru's story and characters are unexceptional but acceptable, with the presence of voice acting being the major factor distinguishing them from concurrent releases on other platforms. By later standards, plot events of all kinds are short and infrequent in Manjimaru. The progatonist says a couple of lines at the beginning and then shuts up throughout the game, while his party members get to talk a little upon being introduced and are subsequently silent except for special occasions. Every boss gets at least a few lines immediately prior to fighting the player, which separates them from other villains at the time but doesn't make them into three-dimensional characters. The wackiness for which Tengai Makyou is known appears sporadically here, one instance being a transformation duel between Kabuki and his rival Kikugoro that owes something to Disney's The Sword in the Stone. Another memorably silly bit finds Gokuraku physically dragging an island by means of magical ropes until it hits the mainland, but the occurrences of such goofiness are infrequent. Like other RPGs of the early 16-bit era, Manjimaru's plot is not the reason to play it.

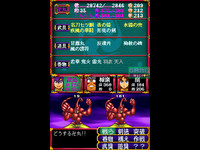

By dint of having animated sequences Manjimaru garnered attention, just like the first Tengai Makyou did in 1989. Seen today these animated portions are far from impressive, as very little movement occurs within them, not even much in the way of mouths opening and closing. The game's approach of using cels that could have come from an animation company instead of sprites in battle is interesting, but only bosses actually move when combat is joined. Regular and magical attacks alike have no animation on either side. The world of Jipang is a large one, and the sprites used while exploring it are capable of doing interesting things. This is balanced by the small sprite size and the frequent reuse of NPC and architectural assets. For 1992 on the Turbo CD it looked pretty good, but time has not been kind, save to the huge number of enemy visuals with little palette swapping.

Things that presage Majin Buu are just the beginning of this game's enemies.

Things that presage Majin Buu are just the beginning of this game's enemies.

|

|

Battle itself is clearly beholden to Dragon Quest. A wildly varied random encounter rate will come down in the favor of incessant combat more often than not, plunging the player into turn-based altercations. Due to the lack of animation in combat, actions are quick to be carried out and killing early foes is usually done in a few seconds. Manjimaru also helpfully puts an Arabic numeral indicating the current HP of every enemy over it in battle, removing any guesswork from the encounters. Kinu also presents something unusual, as she is unable to physically attack or use magic that damages the enemy until very late in the game. Issues start to arise as more time is spent in Jipang, with a significant one being how unpredictably turns for combatants arrive, to the point that participants on both sides may be able to take another action before anyone else gets a chance. Manjimaru's attacks are also prone to missing, something that can affect magical strikes too and seems to happen far more often to the player's detriment than aid. Later skirmishes can take twice the expected time just due to the sheer number of attacks that miss, unpleasantly drawing the proceedings out. The enemies themselves may look goofy, ranging from collections of frog eggs with legs to radioactive cyclops aliens, but as the game progresses they become quite dangerous.

Manjimaru does away with Game Over and simply tosses the player back to a border town in the current province with full health for all when Manjimaru is killed, but overcoming the adversaries will demand copious grinding against the agile hordes. Cash in particular takes a long time to acquire late in the game, when every bit of assistance is necessary to prevail. In this respect the often high encounter rate is a blessing in disguise, because running is rarely a complete success, forcing the player to kill things for their spoils all the time.

Aside from the possibility that offensive spells will miss, Manjimaru manages a quite progressive notion for its age. Instead of magic being gained as characters level up, it is acquired from solitary Tengu mystics living all over Jiping. This method of magic acquisition would be refined in Tengai Makyou III: Namida, but here once a spell is collected it can be freely swapped between the characters. There are provisos, since some spells cannot be used by all characters and a limit on the number of magics each one can hold is present, but the experimentation it allows is welcome. Plenty of spells are relatively useless, but warehouses in numerous towns allow the storage of unnecessary ones.

Manjimaru is not a game to attempt without at least a little Japanese knowledge. Kanji is everywhere, and figuring what items do demands experimentation and remembering the results, because the game does not deign to include any easily-understood clues for those not fluent in Japanese in their terse descriptions. The DS port helps greatly, because it displays a character's current equipment and the numeric benefits each piece conveys on the top screen, thereby relieving players from remembering it while shopping. Only the bare effects of each piece of equipment are displayed instead of the shop window showing whether things are an improvement, which means players must do their own math for every potential purchase. Use of the one English FAQ is highly recommended, because in the fashion of most RPGs at the time goals and the items necessary to achieve them are not always obvious even if one comprehends the language.

Attempting to play this without any Japanese knowledge is not recommended save for those with lots of extra time.

Attempting to play this without any Japanese knowledge is not recommended save for those with lots of extra time.

|

|

Purchasing items is annoying anyway because of the constrained inventory. Each character can hold six pieces of equipment along with expendable items in a separate area. The six equipment slots include what is currently being worn, forcing considerable back and forth item management if more than two good purchases are found in a shop. Manjimaru in particular has a cramped inventory because of his need to carry special weapons in order to kill dangerous plant life, which he must hold until able to deploy them, further constraining his ability to deal with any improved equipment he might find. Other items are mandatory at points for accessing various locations, crimping the ability of the characters possessing them to deal with extra goods.

Figuring out where to go and what to do when there may be problematic, but at least Manjimaru's Jipang is a big place full of things to investigate. An impressive variety of vehicles will be acquired to explore individual provinces while progressing through the game, and the airship capable of crossing all over the land is a massive airborne fortress instead of something more commonly seen. Even by the standards of the early 90s, Manjimaru's game world is impressive in scale, so the use of the DS's top screen for a map while moving around is welcome. Simply wandering around newly accessible provinces to see what can be found is entertaining, such as the unique touch of having plenty of hidden ninja hideouts with free inn services

A number of tracks for this Tengai Makyou's music were composed by Joe Hisaishi, already a veteran of Studio Ghibli work. The majority of the music comes from Yasuhiko Fukuda, later known for Bomberman compositions. The tracks are quite catchy and varied, with a number of battle themes and unique compositions for each vehicle to increase the variety. The voice acting is a more mixed bag, not necessarily for the performances themselves so much as the early state of the technology in video games. Some speech is peppered with pauses and it is very rare to have characters engage in dialogue; rather, they monologue without eliciting a response from anyone. The actors themselves are mostly adequate, with a few exceptions such as Kabuki, who put enough energy into their performances to stand out.

I went into Manjimaru knowing it was extremely popular in Japan with the hope that it would be just as entertaining as its sequels. The second game in the series has unfortunately not aged well, sporting constant frustrations that are difficult to stomach in the present. It has moments of silliness that would be expanded greatly later, but the game itself is not consistently fun to play. At least on the DS helpful information is constantly displayed on the top screen, because without status displays and maps at a glance the original game would be even more of a chore. Every other Tengai Makyou game I've played is a goofy delight, but this one is a relic.

Review Archives

|